Looking at the rubber duck:

Nicolas Roeg on François Truffaut

Nicolas Roeg talks to Richard Combs about working with François Truffaut on Fahrenheit 451, in the Winter 1984/85 issue of Sight & Sound

I’ve always felt that, although Truffaut was greatly revered and admired, at the same time, in terms of film and how much he loved film, he was underestimated. Because he was known to be a literary man, someone who was enormously fond of literature, he was adopted by a very literary set. But in fact his love of literature was separate from his love of film. I think that’s why, many times, he has been underestimated as an essentially visual person. I enjoyed working with him tremendously on Fahrenheit 451, which was a film very much to be ‘read’ in terms of images. I suppose he was the first director, the first film person, with whom I’d enjoyed having a conversation about film, or the hope of film. There weren’t many about in those days.

I remember there was a lot of criticism of Fahrenheit to do with François’ knowledge of English. The critics complained that it was so stilted. But that had all been quite deliberate. He hadn’t even wanted to place it as an English film, or to suggest that the language was necessarily English. The script was written first in French, deliberately, so that it could be translated into English, then translated back into French, because he wanted to lose the English idiom completely, then finally translated back into English. He wanted it set- and I thought this was a marvellously futuristic idea – in a time when people had lost the use of language. After all, the whole premise of the film was to do with losing a literary background. And that was completely missed by the critics.

There was even one little clue which Truffaut put inside the film, because he didn’t want this to be mistaken. There was a scene where Montag and Clarisse are sitting talking; they can see the fire station, and a man comes up and puts a note through the letter box. Montag explains why that is, people reporting on each other. Clarisse says, oh, he’s just a common informer; and Montag says, informant. Stilted things, stilted phrases: that was absolutely putting the dot on the ‘i’. We’ve even seen that sort of thing come to pass. Language is flattened slightly. You see it in films: in the 1930s and 40s in America they used words in films that they wouldn’t put in a script today. I don’t know whether it’s an apocryphal story, but apparently when George Cukor did a remake ofOld Acquaintance as Rich and Famous, they did research into the title, and hardly anyone in America knew what an acquaintance was.

François was aware of that, and he realised that images were things to be read. Like the scene where Montag is sitting in bed with comics. Those comics were very carefully designed; they were a form of shorthand, so that the news could be read in pictures. The beauty of the language wasn’t what was important. It was like a rather intimate film where language means a lot, but we no longer have the language. So you virtually have to read the pictures. It implies there will come a time when people will still have all those emotions, but you have to read through other indications, other signs. It was a sign language once, and maybe we’ll go back to that.

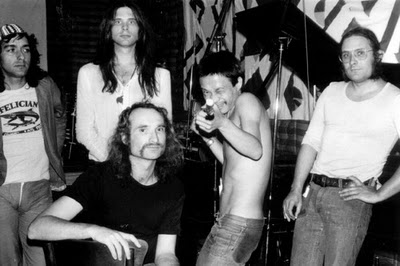

Nicolas Roeg (left) and François Truffaut (right) on the set of Fahrenheit 451

François thought the stranglehold of the written word was going to be equalled, if not superseded, by the idea of images. I guess it takes a long time; he thought it was coming quicker. But in some ways one forgets how quickly things have changed. For instance, he wanted no written signs, and in the fire station there was nothing written. It was very difficult to work those signs out. But think about how road signs have changed. Once when you drove down the road you’d have to read dozens of things – road bears to the left, school ahead – but now they’re just children with a stripe through them, so we can drive anywhere in Europe. At the same time that was a very filmic thought: the essence of film. I’m sure that was why he was attracted to the story.

I’d hate it to be forgotten just how much of that kind of a filmmaker he was. Not just charming stories and enchanting acting. For instance, he wanted to make a film with small children, babies, just to get their expression at the point when words aren’t quite understandable. We had a scene in Fahrenheit with a baby lying in his pram in the park, and the fire chief turns him over and finds a book underneath. Another aspect of that is the scene at the end with the book people – who are all wrong. The veneration of literature – which he loved – is all wrong. The boy who is reciting from Stevenson, reciting after the old man, has got it wrong. And there are twins who announce themselves as Pride and Prejudice, Part One and Part Two, but of course there isn’t a Part One and Part Two in Pride and Prejudice. All these things were missed by the very people who had revered him as a literary filmmaker.

It’s the same thing with acting. Oskar Werner – who tragically also died a few weeks ago – was at the time, as I remember, just starting to enter a successful, commercial stage of his life. And he was rather concerned about his image. It appeared to be, or I surmise, that Oskar thought this was a film he was doing for François, because he owed him something or he liked him. But at that stage of his career he just wanted to get it over with. To play the part of Montag, you have to be completely dedicated to the thing. So he didn’t enter fully into the film. But François won in the end; he had to, again by the use of film, by juxtaposing one thing with another. Whatever meaning you tell me you are putting into that performance, I shall change it by making you look at a rubber duck. If you look seriously at this man when I want you to be smiling, because I want you not to understand what is happening, I shall use that serious look. I shall make you be looking at a rubber duck while he is talking. So that you will look seriously as if you don’t understand.

Every single piece in the construction of the film was visual. I remember when the art department brought a beautifully made model of a fire engine into the office of Cyril Cusack, who played the fire chief. It was like the model that a ship’s captain would traditionally have had in his cabin. But François said, no, no, go to a toy shop and get me a toy. Because that sort of skill is already gone from the world. It was a toy world in which all the skills had been lost. When we discussed the look of the film, he said, I don’t want it to have a reality, I want it as a Doris Day film, with little shining colours. We had great trouble, because at that time people were going for a tremendous realism. I was ordering huge brutes, to make it high key, glossy, like Technicolor.

He also wanted a certain sense of awkwardness in behaviour patterns. After all, things change subtly. I’ve always noticed that films set in any sort of future very rarely draw on the present. But just imagine someone a hundred years ago trying to predict the present. I live in a house that’s a hundred years old. Its internal functions are different, the carriages outside are different – but it’s a mixture. Things don’t all go away. That’s why we began Fahrenheit with those aerials and things on top of suburban houses, although inside the houses are sliding doors – which don’t work… Changes are so subtle: relationships, manners, our behaviour. I thought it was quite a frightening film in that respect. But it’s very difficult to read that. It’s easier to see something you can be totally in awe of. Something which is part of your life and has taken on another aspect is much more difficult to believe in.

François was rather sanguine about the failure of Fahrenheit, critically and commercially. One time when we were having dinner he said, it must have been a bad film. I asked why? He said, nobody went to see it. In terms of his filmmaking, I don’t think he pulled back after that at all. But Fahrenheit might have been a stretch which he was not given the chance to do again. And he wasn’t a man to explain himself. He’d rather go on: a futuristic present-day person. He was wonderful about the past. He told me how he hated costume pictures where they tell you these were the clothes they wore from 1490 to 1498, and then these clothes were worn from 1498 to 1502. He said, I like to have a lot of clothes, sort of turn of the century, and just put them in a basket and have the artists try some of them on. After all, the jacket I am wearing is 15 years old. I am not always in fashion.

‘Fahrenheit 451’ screens in the BFI’s François Truffaut retrospective, 4 February–28 March at the BFI Southbank